History & Heritage 2014

FEBRUARY 2014: THE JAPANESE CONSULATE INCIDENT

By C. S. Papacostas for the February 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawaii

About the same time as C. S. Desky's Progress Building was completed at the makai-ewa corner of Fort and Beretania Streets in Honolulu, Desky was reported to be "superintending for Bruce Cartwright the erection of an annex" to it for which ground was broken the previous day [Hawaiian Gazette, HG, 5/6/1898].

Called the "Model Building" or "Block," it shared the makai wall and electric elevator with the Progress Building. It was three stories in height and was made of "island stone and brick and iron, with plate glass stone fronts," just like the Progress Block. It had a frontage of 63 feet on Fort Street resulting in a combined 146 feet for the two buildings and a depth of 80 feet. The two buildings were so similar that they became indistinguishable from each other and had been often referred to collectively as the "Model Progress Building" to this day [Star Bulletin, SB, 2/22/2004]. Contrasted with the architectural drawing of the Progress Block I included in my article of two months ago (December 2013), the recent photograph below illustrates this point.

A shortage of imported cement that caused the local price to jump from $2.40 to $5.40 per barrel caused unexpected delays in the construction of the Model building as well as an addition to the Bishop Museum that was also under way at the same time [HS 5/23/1898]. Cartwright had paid Desky $12,000 for the 4,976 square foot property to construct the building at an estimated $32,000 according to plans prepared by Desky "with a few changes [Hawaiian Star, HS, 4/26/1898]." It appears that before Cartwright entered the picture "Los Angeles capitalists" had secured an option from Desky to construct a four-story brick building designed by architects Howard & Train but uncertainty about annexation of the islands apparently discouraged them from proceeding [HS 1/25/1898]. Plans by Desky for a "big hotel adjoining the Progress block" were also dropped [HS 2/3/1898].

A shortage of imported cement that caused the local price to jump from $2.40 to $5.40 per barrel caused unexpected delays in the construction of the Model building as well as an addition to the Bishop Museum that was also under way at the same time [HS 5/23/1898]. Cartwright had paid Desky $12,000 for the 4,976 square foot property to construct the building at an estimated $32,000 according to plans prepared by Desky "with a few changes [Hawaiian Star, HS, 4/26/1898]." It appears that before Cartwright entered the picture "Los Angeles capitalists" had secured an option from Desky to construct a four-story brick building designed by architects Howard & Train but uncertainty about annexation of the islands apparently discouraged them from proceeding [HS 1/25/1898]. Plans by Desky for a "big hotel adjoining the Progress block" were also dropped [HS 2/3/1898].

Despite their outward uniform appearance the Model and Progress buildings remained separate entities. Among the occupants of the Progress Building were the U. S. War Department, the Democratic Party and the YWCA. When the Japanese Government purchased it from the German Savings and Loan Society of San Francisco in early 1907 [HS 1/22/1907] intending to use it as its Consulate, an international incident ensued. The Consul General of Japan, Miki Saito, started to partition the two buildings, a move that could cut off the tenants of the Model Building from the use of the shared elevator. Desky protested but Saito remained "firm in his decision" and thought that Desky had "no business in matters pertaining to Japanese territory [HS 2/9/1907]."

The same source speculated "several other interesting situations in regard to the renting of the stores on the ground floor. This property is Japanese territory. Now when goods are taken into the stores there the Japanese government should collect duty on them. Then when they are resold to customers, a custom house officer will have to stop them at the door and demand duty. The stores will be taxed by the Japanese government and the United States can only collect duty on the objects as they come from the premises in the arms of customers."

During the fracas Consul General Saito determined that "there was a contract between the former owner of the Progress building and the owner of the Model building to the effect that the tenants of the Model building should be allowed to use the elevator and while the contract remains valid, the Consul General will not deny the use of the elevator to tenants of the Model Building. [HS 2/11/1907]."

As for the jurisdictional issues relating to the rental of stores, this issue apparently petered out as the Japanese government ended up occupying the entire remodeled building: The first floor by the offices of the consulate and the upper floors for the Consul General's residence, along with "a large banquet room [and] a commodious reception room [HS, 5/4/1907]."

The Model Block also changed hands several times. For instance, it was sold to a Mrs. Annie S. Park for $32,000 on March 16, 1911, and later by her heirs for $45,000, the upper floors occupied by the U.S. District Courts [SB 4/13/1913]. A contemporaneous proposal "to purchase both the Model and the Progress buildings for a combined amount of $122,000... for use as a city hall" apparently fell through, even though "the buildings are already connected with an elevator, not now in service [HG 3/7/1913]." By the end of April, "the sale of the Japanese consulate general, known as the Progress block" was to be "consummated to the C. M. Cooke Estate, Ltd at $65,000 [SB 4/19/1913]." According to earlier speculation, "removal of the Japanese consulate general from its present quarters, occupying with the Japanese mercantile museum the entire Progress Building..., to Nuuanu avenue, near its original location... upon the old Waterhouse homestead on Nuuanu avenue [SB 1/14/1913]." Presently, the Model Progress Building is occupied by Hawaii Pacific University. On a recent visit, I determined that the interiors of the buildings had been almost totally gutted and replaced with modern facilities, only several load-bearing brick walls having been retained. The original entrance to the upper floors on Beretania Street has been filled in and a modern fourth floor, hardly discernible from the street, has been added where the original roof garden was. Modern elevators, on the side of the Model Block this time, have replaced the original that became a bone of contention many years ago.

MARCH 2014: 1890s BICYCLE CRAZE

By C. S. Papacostas for the March 2014 Wiliki o Hawai`i

In outlining the history of land transportation in the United States in my 1987 "Fundamentals of Transportation Engineering" book, I related the fact that "toward the end of the nineteenth century, a good-roads movement swept the country" and that "newly formed associations of recreational bicyclists who had begun to brave the countryside played a pivotal role in this movement." Involving emancipated women, this national good-roads movement was called a "bicycle craze."

Consistently, when the Honolulu Road Club, an organization of progressive bicyclists, issued its inaugural salutory in 1896, it declared, "there is no reason whatever why Hawaii should not have many more miles of good roads, and especially so throughout the island of Oahu... Remember, it is productive of less damage and more profit to drive over twenty miles of hard, smooth road such as are in parts of Honolulu than to drive over one mile of poor road such as many be found in many parts of Oahu [Hawaiian Star, HS, 9/30/1896]."

But how did we get there?

As early as October 23, 1847, in a Polynesian newspaper adverisement, Everett & Co. offered for sale "the cargo of the ship 'Medora,' just received from Boston," that included "velocipedes." Whatever the term referred to in that context, it does not appear to have caught on. Almost twenty-two years later, on January 27, 1869, the Hawaiian Gazette (HG) told its readership that "Mr. C. P. Ward has received from San Francisco one of those vehicles known as a velocipede, whereon a person can, by the action of his feet alone, propel himself over the ground at a rapid rate." On June 12 of the same year, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser (PCA) printed a long article titled "My Experience with a Bicycle." Extracted from the monthly "Maile Wreath," it described humorously the anonymous author's first experience with a velocipede featuring a large front and a smaller rear wheel. Describing it as an "unmanageable animal," the author recounted a few trivial falls and an out-of-control run off the road, down a steep hill and into a taro patch.

"When velocipedes were first introduced here, he has the credit of riding the first one perfectly in public... and nearly all Honolulu turned out to see him ride on King street," said The Independent [3/13/1902] in its obituary of notable royalist William Auld who was born in 1842 in Honolulu. If this event happened in 1869, Auld was 27 years old at the time of his feat. On March 5, 1870, the PCA announced that at a local circus show "the closing exhibition of the evening will be a Velocipede Race between a number of our Honolulu youngsters, who have acquired more or less skill in riding this new fashioned engine of locomotion."

By the end of 1880, Brewer's on Fort Street listed among its wares both velocipedes and bicycles and in 1982, the Kapiolani Park horse racing track was scheduled to also feature "a bicycle, tricycle and foot race for 200 yards [Daily Bulletin, DB, 4/19/1882]."

The PCA of April 28, 1883 discussed the bicycle as a serious transportation mode saying "we have noticed but one fine bicycle in use in this city." Calling it an "iron horse," it encouraged the organizing of a club devoted to the "science" of bicycling because it was "a convenience and a healthful mode of exercise." It noted that "the cost of one would soon be saved in fares paid to cab drivers" and the level roads especially to Waikiki were presented as an added inducement to such ownership.

A few months later, the Daily Bulletin [DB, 12/15/1883] reprinted a New York World description of America's first exposure to "England's New Bicycle" as follows: "The steamer Persian Monarch brought over a bicycle ridden and manufactured on far different principles than any known to the American public. The wheels are uniform in size, the rider sitting between the wheels and balancing himself on the axle. It is propelled by the feet revolving on a crank, to either side of which is affixed a pulley connected with the hubs of the two wheels by steel driving bands." Moreover, "the machine can be stopped without dismounting." Called the "Otto" it was reportedly "brought over by A. P. Barlett of London."

On new year's day in 1885, a series of athletic sports held in Makiki included a five mile bicycle race [DB 1/2/1885]. Three years after the PCA urged the initiation of a bicycle club, a paradoxical line appeared in the March 11, 1886 issue of the DB: "Somebody with a large head thinks a bicycle club would pay well in Honolulu." As if in response, the same paper explained on April 14, 1887, "the reason why there is no bicycle club in this Kingdom is that a portion of Queen street is about the only course in the realm where the two wheels safely run away with a man."

Considering the subsequent popularity of this "machine," one would assume that it had no detractors, but according to the DB of Dec. 19, 1890, "the bicycle has been slated in Newark as an instrument of evil" and a congregation gave a clergyman the ultimatum of either giving up riding or withdrawing from the church!

On November 29, 1892, the DB reported that "one of the prettiest spectacles ever seen on Honolulu's streets was the parade of the Pacific Wheelmen on the evening of Independence Day. About thirty bicycles illuminated with Chinese lanterns were on line... Her majesty presented the corps with a cheque for $50 for the erection of a fence around their new track at Pearl City. The track is situated opposite Mr. John F. Colburn's place on ground as level as a billiard table." Less than two months hence, on January 17, 1893, Queen Lili`uokalani's govenment was overthrown.

The Pacific Wheelmen had adopted their constitution and by-laws on Sept. 29, 1891. Among the initial 25 members were Cupid K. Kalanianaole (Kuhio) and his brother David Kawananakoa [HG 10/06/1891]. The club sponsored bicycle races along King Street, some of which were reserved for its own members and others "free to all." The first "gold medal was won by Ruby Dexter, riding a Rudge safety" on April 30, 1892 and Prince Kuhio tied for fourth place [DB]. To raise funds for their track, the Wheelmen organized moonlight excursions and picnics at Remond Grove Pavilion, twelve miles west of Honolulu to which Dillingham's Oahu Railway & Land (OR&L) Co. provided regular service. Being a "temperate lot," the Wheelmen "dealt out temperance drinks and sandwiches liberally for a small considertation" under "the mellow glow of electric lights [DB 3/6/1893]."

Bicycle use must have picked up the pace about that time for, in describing a football game won 26-6 by Punahou over Pacific on February 18, 1893, the HG [2/21/1893] pointed out that "quite a large party of young ladies, evidently belonging to a bicycle club" were in attendance. Later in the year, the same newspaper averred prophetically, "as there is already a lady's bicycle club organized here it is expected that the present importation [of bicycles] will increase the interest therein [HG, 7/18/1893]."

On June 30, two Pacific Wheelmen received positive publicity for completing 80-90 miles around O`ahu and reporting that the road was good. They were President H.E. Walker and Secretary-Treasurer W.M. Bush [DB 6/30/1893].

As we shall see next, the safety bicycle finally took Hawai`i by storm.

MARCH 2014: 1890s BICYCLE CLUB GROWTH

By C. S. Papacostas for the May 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

Two months ago (March 2014), I concluded my article with a prediction by the Hawaiian Gazette (HG) of July 18, 1893 that, given the fact that a ladies' bicycle club had been organized in Honolulu, the use of bicycles would show an upturn.

Around the same time, marketing their individual brands, several agents of bicycle manufacturers started membership clubs that offered those who joined special deals toward purchasing their bicycles. The Cleveland Bicycle Club, for example, announced that "it will cost you $10 a month to be in line with other 'Cleveland' riders" and that a drawing was to be held on April 1, 1894. Later in 1894, the Rambler bicycle agency started its own club offering "a good wheel by paying $2.50 a week," and a drawing every other week for one of its light-weight bicycles. Other brands with their own clubs were the Union, the Meteor, the Remington and the Reliance Clubs. Among other brands mentioned in the newspapers were Barnes Whiteflyer, Eldredge, Victor, Crawford, Elfine, Waverly, Monarch, World and Hawaii, the last one being locally made by the Hawaiian Cycle and Manufacturing Company!

The Pacific Wheelmen club that was established in 1891 continued to organize "drills" and other events. On December 9, 1892, they accompanied a "far-famed wheelman" named Maltby who rode his device only on its large wheel through town [Daily Bulletin, DB, 12/8/1892] for the enjoyment of large crowds [DB 12/10/1892]. Another notable event took place on August 19, 1894 that consisted of a 35-mile ride from the Opera House in downtown Honolulu to Moanalua and back to town, continuing to San Souci in Wailiki. "After having a dip in the brine and polishing six watermelons," they returned to town where they had a group photograph taken [DB 8/20/1984].

A new unaffiliated bicycle club called The Honolulu Cycle Race Meet Association was announced on Oct. 6, 1894 in the newspaper Hawaii Holomua [HH]. This club planned a meet at the Kapiolani Park horse racing track for Thanksgiving Day but postponed it to Christmas Day later in the year. This time as a member of the "Ramblers," Prince Kuhio participated and placed second in a half-mile open race [DB 12/16/1894].

Between the establishment of this association and its first meet, a milestone event occurred that spurred local interest in bicycling further: Two renowned racers, G. A. Griffiths and H. F. Terrill, arrived in Honolulu from San Francisco by the bark Albert in the morning of October 27, 1894. On the occasion of their arrival, the HG of Nov. 2, 1894 noted that "less than ten years ago a bicycle was a curiocity. Now the safety is a part of every day life." Welcomed by the Pacific Wheelmen, the visiting aces entered a 10-mile race from Palace Square (renamed to Union Square after the overthrow of the Kingdom) to Waikiki, around Kapiolani Park and back. Griffiths was clocked at 26 min and 35 sec., Terrill at 26:37, and the first local finisher, Jack Atkinson, at 27:57. Prince Kuhio was among those who were unable to finish the race because "his seat turned over near the park and so threw him out [HS 11/26/1894]."

Subsequently, "the interest aroused by the road race given while the San Francisco flyers were in town, has not by any means abated [HS 12/24/1894]." With it came the need for riding schools and repair shops, reports of mishaps and collisions with horse-drawn carriages and between bicycles, and incidents such as "shortly after noon today Detective Kaapa arrested Kahana, a native boy who stole Young Min's wheel [Evening Bulletin, EB 8/5/1898]."

A report that 282 bicycles were imported during 1895 reinforced the fact that "the 'bike' is not a luxury but a necessity [HG 4/21/1896]." A concern that "the Japanese are making bicycles far cheaper than anyone else in the world" was expressed by the same source, "but then it does not suit us to buy Japanese bicycles."

The year 1896 saw the formation of more bicycle clubs.

The first of these was an "organization of progressive bicyclists" named The Honolulu Road Club boasting 25 members on Sept. 29, 1896. As I mentioned last month, this club called for the construction of good roads after the fashion of its U.S. mainland counterparts. On the next day, the intent of noted bicyclist George Angus to form a second club was announced [HS 9/30/1896] and by the end of the next month, a local racer named John Sylva, dubbed the Manoa Wonder, was reported as "organizing a cosmopolitan bicycle club" with special encouragement offered to "native riders [HS 10/26/1896]." In the meantime, the pre-existing Honolulu Amateur Athletic Club (HAAC) had opened its annual field day to bicycle racing by members of the various clubs after addressing internal disagreements between "athletic and bicycle club members [Hawaiian Star, HS, 1/21/1897]."

At this point I realized that, besides the competition between manufacturers, the proliferation of bicycle clubs had to do with the social conditions prevailing in Hawai`i at that time. Thus, the Pacific Wheelmen I discussed last month were sympathetic to the Christian Temperance Movement, the members of the Honolulu Road Club were reportedly adherents of the Progressive Movement, women groups were connected to the Suffrage Movement, whereas the latest club admitted many native Hawaiians to its ranks. Japanese and Chinese residents were reported to own and use bicycles, but the first mention of a Japanese Bicycle Club or Association I discovered was much later [HS 12/31/1903] and no such reference to a Chinese club was found.

The racial distinctions of those times are also underlined by a statement from an apparently informed "prominent wheelman" who expressed his frustration about a failure to raise funds to build a bicycle race track in town: "There are 2074 Americans in the city, the British number 1308, the Germans 578, the Portuguese 3833. Taking Europeans of all races, and Americans together there are in the city of Honolulu 8397 whites. Out of this number there surely is one thousand sport loving people who can afford and ought to pledge themselves" to contribute [HS 3/13/1897]!

The events leading to this statement will appear in the next installment.

JUNE 2014: CYCLOMERE LAKE

By C. S. Papacostas for the June 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

After he read one of my recent articles, Goro Sulijoadikusumo wrote "Just read your great article on bikes as I've been away in Patagonia," and he referred me to a book by David Herlihy titled "The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance" about German-American Frank Lenz who rode his bicycle around the globe. While in Honolulu in 1892, "Lenz called on George Paris, a former resident of San Francisco and the local agent of Columbia wheels. The two wheeled up Punchbowl Hill, taking in a magnificent panoramic view of the surrounding islands. In the distance, Lenz spotted his vessel, bobbing like a toy in a tub. In the city center, Lenz photographed himself and his bicycle before the Iolani Palace."

Four months ago, in February 2014, I had discovered and reported that the Pacific Wheelmen, who organized in 1891, had plans to complete a bicycle track, "level as a billiard table," in Pearl City, but I was unable to determine whether the facility was ever completed. At that time, bicycle racing was organized along King Street. The "silent steed" also invaded the horse racing track at Kapiolani Park, "the beautiful suburban resort," as the Daily Bulletin [DB 12/16/1894] put it. By 1897, "cycling [had] taken the lead of all other sports" in Honolulu [Hawaiian Star, HS, 2/16/1897].

Considering the explosion in the use of the safety bicycle, it was inevitable that attempts to construct a bicycle track in accordance with scientific principles (e.g., superelevated curves) would follow, as it had been the case in other cities. This must have been the talk of the town for in a short span between the end of March and the middle of September, 1896, not one but three proposale were advanced.

On March 25, 1896 the HS described a proposal advanced by Tommy King of the Hawaiian Hardware Co. (importer of the Tribune bicycle) to modify the then existing Makiki baseball grounds by adding a half-mile race track and a quarter-mile bicycle track, with a baseball ground in the center.

According to many sources, an earlier baseball diamond at the Makiki Recreation Grounds (also referred to as the Parade Grounds) was the first in Hawai`i. It was laid out in 1852 by Alexander Joy Cartwright, the "father of modern baseball" who came to Hawai`i a year earlier. This field, bounded by Ke`eaumoku, Lunalilo, Makiki and Kinau Streets, became the venue for baseball, cricket, football, association football (soccer), field games, military exercises and other events such as "balloon ascention by skilled aeronauts [DB 11/23/1888]." The athletic event participants included local teams and teams from civilian and naval ships visiting the harbor. In 1938 the 2.96 acre place was given its modern name, Cartwright Field, in recognition of Alexander Joy's induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Tommy King's 1896 proposed plan would have modified the area west of the Cartwright Field and "bounded by Lunalilo Street on the North, Keamaku [Ke`eaumoku] on the East, Kinau on the South and Piikoi on the West." The 1897 Map of Honolulu by M. D. Monsarrat designates this area as "Baseball Field" and the Cartwright Field as "Parade Grounds." With an entrance at Piikoi Street, the private baseball field was built by a "Base Ball League" and had its inaugural game on Nov. 17, 1890 when a local team lost to a California team 12-1. Unlike previous free games at the public recreational grounds, the league charged admission of 50 cents with a 25-cent extra fee for a reserved seat in the 1200-seat grand stand [DB 11/28/1890].

A second proposal for a bicycle track was announced on Sept. 10, 1896: "Bruce Waring & Co. will present to the H.A.A.C. [Honolulu Amateur Athletic Club] a proposal to make a bicycle track and sporting ground on the tract at Kewalo." As I mentioned in Dec. 2013, this was a real estate company that employed entrepreneur Charles S. Desky, the developer of the Model/Progress Building, among other ventures. The reclamation and subdivision of the Kewalo tract was one of the company's projects that included the construction of a pond to receive the area's drainage. Targeting the $200 lots for "people of moderate means [Hawaiian Gazette, HG, 1/5/1897]" the company had solicited first-come, first-serve "applications for lots in the Kewalo tract just back of the Kawaiahao church [HS 9/8/1896]."

Notice of the third bicycle track proposal came in the Evening Bulletin [EB 9/14/1896]: "A proposition is afoot to the establishment of a quarter mile bicycle track around the ball grounds, for which there is plenty of room. Messrs. Fisher, Allen, Spencer and others are looking up the matter."

To advance his company's plans, Desky "was met at the Hawaiian Hotel Wednesday evening by about two dozen members of the H.A.A.C. and members of the new Honolulu Road Club [that I discussed in March 2014], to whom he submitted his proposal regarding the much talked of bicycle track at Kewalo near the old head of Kawaiahao lane. The proposition in a nutshell was: To lease the seven acres for fifty years at a rental of $1, the cyclists to keep up the property, pay the taxes, etc.; or to sell the property in fee simple for one-third the cost of constructing the drain pond and reclaiming a plot of twenty acres. The latter proposal would contemplate an outlay of about $2,000 before actual work on the track begins. Then there will be a track or tracks to lay out and grand stand and fence to be built, which will bring the cost to several more thousands. The drain pond will be five acres and oval shaped. This will leave a space fifty feet all round for the tracks and will afford a fourth mile wheel course [HS Thursday 10/1/1896]." A committee of five was appointed to follow up and "plans of raising the money had been suggested."

In a letter to the HG on the next day, Lorrin A. Thurston, leader of the Hawaiian Kingdom's overthrow and annexationist, proposed to organize a stock company to raise the funds for the procurement of the land, track and buildings.

About the same time, the real estate company's marketing campaign declared a contest "to the person who selects the most appropriate name for the lake now in construction inside of the bicycle track at Kewalo will receive a deed to one of the [50x100] building lots." Whereas I was not able to discover the winner's name, perhaps because of a desired anonymity, the name of the artificial lake appeared in the Hawaiian Gazetter of Feb. 23, 1897:Cyclomere Lake (see attached 1897 map excerpt of the Kewalo tract).

JULY 2014: CYCLOMERE PARK

By C. S. Papacostas for the July 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

On the occasion of the establishment of League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W) on May 31, 1880 at Newport, Rhode Island, the New York Sun [6/1/1880] had declared, "the growth of bicyclism has been very rapid of late in this country, and amid all the talk of new motors, it is fair to say that the bicycle is the one modern machine which has come nearest to solving the problem of personal rapid transit." That was, of course, before the proliferation of the private automobile that claims that distinction to this day.

In 1894, the national L.A.W. banned all but whites from membership. Consistently with the social mores of the day, it had also been advocating for the abolition of bicycle racing by women. As the Hawaiian Star [HS 8/14/1896] rationalized, "it is presumably for excellent reason that the Racing Board of the L.A.W. has announced that it will blacklist any bicycle track upon which female riders are allowed to contest before the public" and, in a widely reprinted article originating with the New York Sun, "Racing among women ought to be abolished... Moderate wheeling invigorates the system, strengthens the muscles and increases physical endurance, but excessive wheeling is positively injurious and shockingly unwomanly [e.g., HS 9/5/1896]."

Other racing restrictions reported in the press included "the railroad's track at Santa Monica is blacklisted for allowing Sunday racing [San Francisco Call 12/12/1896]."

So called Sabbath, Blue or Sunday Laws have a long history. They were even encoded in the Hawaiian Laws accompanying the Constitution of 1840 and prohibited "all unnecessary worldly business" as well as "all worldly amusements and recreations" and also "all loud noise, and all wild running about of children" on Sunday. When the Pacific Commercial Advertiser (PCA) advocated for the relaxation of Hawai`i's Sabbath laws to allow ships to coal, discharge or take freight on Sunday, the Hawaiian Gazette (HG) of May 13, 1874 retorted: "It is enough to say that Christian principles require the day to be set apart from ordinary business." The debate continued unabated and in 1898 the Independent [2/2/1898] editorialized, "We hope that one of the first measures taken up by the Legislature will be the repeal of or at least a radical amendment to the present Sunday Laws."

It was within this social milieu that C. S. Desky pitched his idea to Honolulu's white male bicycle riders on Sept. 30, 1896. As I talked about last month (June 2014), Desky's idea for a bicycle track around a drainage pond, named Cyclomere Lake, in the Kewalo tract subdividion of Honolulu was gaining traction, so to speak, toward the end of 1896. In response to these proposals, annexationist Lorrin A. Thurston put together a committee to negotiate with Desky for the track, a rough description of which appeared in the Hawaiian Star (HS) of Jan. 7, 1897:

The plans called for a track, grand stand and club house, and a small island covered with plants, flowers and greens and featuring the highest flagstaff in Honolulu was to occupy the center of the 5-acre oval pond. The Thurston committee presented their findings at a meeting on Jan. 27 where he was elected Chairman of the Kewalo Basin Track Association and a five-member organizing committee was put together over the next few days. It included A. B. Wood, the president of the YMCA, and W. W. Harris, the president of the Honolulu Road Club. The committee met with surveyor W. A. Wall to discuss the project and agreed the "Kewalo soil will make excellent topping for the track. The soil packs well and is hard as cement when rolled [HS 2/11/1897]."

By Feb. 23, the editors of HG became impatient at the lack of apparent progress: "The time for closing with Mr. Desky on his proposition has passed by long ago," they warned. On the 26th, the HS announced a change in committee membership, including a new Chairman, W. F. Allen, and an estimated cost of track, grand stand and other buildings of $10,000. On his side, Desky was reported to be "anxious over the proposition. He vows that unless the wheelmen do something shortly, he will go ahead himself and build the track [HS 2/16/1897]." Fund raising was not as easy as expected and "enterprise falls through for lack of funds," declared a headline [HS 3/13/1897].

Interestingly, at that point the Honolulu Road Club made an independent offer to Desky asking him to build the track and lease it to them for a brief period. Desky determined that this offer did not make business sense for him, and refused.

A month later, a group of investors led by Henry E. Walker of the Cleveland bicycle agency announced a scheme to build a one-sixth mile wooden track somewhere in "Upper Beretania." It would be "15 feet wide with the exception of the home stretch, which will be 20 feet. It will be banked on the turns to the height of 6 feet and on the straights from 1.5 to 2 feet [HG 4/23/1897]."

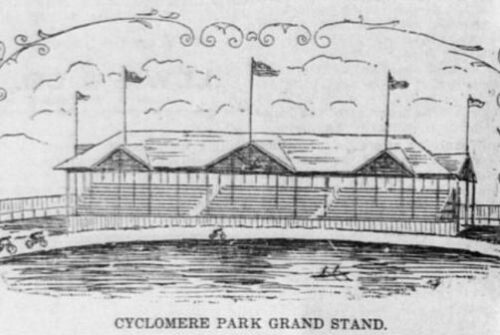

Desky proceeded to negotiate with both competing groups and finally reached an agreement with the Walker association for a rental of a board track, grand stand and other buildings at a yearly amount of $200 on a tract of land at Kewalo separate from Cyclomere Lake that would feature night racing by electric light, a relatively new technology. The boards lining the track were to be "battens, one inch thick, three inches wide and twenty feet long [HS 5/29/1897]." Curiously, only a month later, Desky and Walker arrived at an agreement to disband the Bicycle Track Association and to "build the track as a private enterprise" on 4-acre tract on the Waikiki side of Cyclomere [HS 6/26/1897]." The specifications for this one-sixth mile facility included a wooden track, 18 feet in width with a 23-foor stretch, outer edge 6 feet higher than inside edge, grand stand with 500 seats and private boxes as well as dressing rooms and training quarters underneath.

Although contractor Chas. D. Walker was selected for the job, these plans also fell through for Desky ended up building the track on his own as originally envisioned, around the lake, featuring a clay soil surface, 25 foot wide with 40-foot home stretch, a grand stand for 800 people, and "powerful electric lights" to be spaced 100 feet apart [HG 7/27/1897]. Contractor W. H. Cummings replaced Charles Walker and W. A. Wall surveyed the now shortened to one-third mile track. The course was banked on the backstretch "2 feet in 25, just enough for drainage, while at the other turn just before entering the home stretch [was] 6 feet in 25, much less than some tracks in U.S. [EB 8/4/1897]." The surface treatment was described as "natural cement taken from the bottom of the lake... This cement is nothing but decomposed coral and it is thought to be superior to the manufactured cement of which many Eastern tracks are composed."

An advertisement by Tribune Bicycles in several papers referred to the Kewalo Bicycle Track as Cyclomere Park and soon thereafter "Desky appointed C. L. Clement sole manager [HS 8/20/1897]."

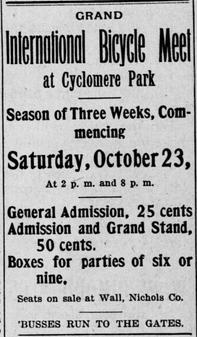

The opening night was finally set for Saturday, October 23, 1897.

AUGUST 2014: OPENING OF CYCLOMERE PARK

By C. S. Papacostas for the August 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

Charles S. Desky's Cyclomere Park, a track exclusively devoted to bicycle racing, opened on Oct. 23, 1897 with two meets, one in the afternoon commencing at 2:00 p.m. and another in the evening at 8:00 p.m. under 23 large 2,000 candle arc lights. Almost twice the 12 originally envisioned, they were powered by the Hawaiian Electric and Light Company. Walter C. Weedon, Desky's fellow employee at the Bruce Waring Co., was identified as a co-promoter of the park and the company constructed a private pavilion on the grounds [Hawaiian Gazette, HG 10/19/1987]. Being the entrerpreneur that he was, Desky contracted "crackerjack riders" from the Coast "to be present at the opening of the track [HG 10/12/1897]. They were professional riders Allan W. Jones, Dan E. Whitman and George Sharrick (spelled alternately as Sharick and Sharack), amateur Trilby Fower and their manager, L. L. Conkling, the head librarian of the San Francisco Law Library [Hawaiian Star, HS 10/21/1897]. General admission for the "International Bicycle Meet" was set at two bits (25 cents), whereas admission to the grand stand was set at 50 cents; individual tickets as well as "boxes for parties of six or nine" were available for sale at Wall, Nichol Co. and "'busses [read, "omnibuses"] run to the gate."

Being the entrerpreneur that he was, Desky contracted "crackerjack riders" from the Coast "to be present at the opening of the track [HG 10/12/1897]. They were professional riders Allan W. Jones, Dan E. Whitman and George Sharrick (spelled alternately as Sharick and Sharack), amateur Trilby Fower and their manager, L. L. Conkling, the head librarian of the San Francisco Law Library [Hawaiian Star, HS 10/21/1897]. General admission for the "International Bicycle Meet" was set at two bits (25 cents), whereas admission to the grand stand was set at 50 cents; individual tickets as well as "boxes for parties of six or nine" were available for sale at Wall, Nichol Co. and "'busses [read, "omnibuses"] run to the gate."

To further spur interest, Cyclomere manager Clement invited "Everett Turner, the Hilo 'surprise' [who claimed] the fastest record from the Volcano house to Hilo" to face "Manoa Wonder" John Sylva in the opening meet. Turner declined but wrote nevertheless that "he stands a fair chance among the cracks of Honolulu [HS 9/21/1897]." Manoa Wonder and other Honolulu riders were training in town and were seen "speeding on the Waikiki road every afternoon [Evening Bulletin, EB 9/4/1897]." On Oct. 20, 1897, the HS listed all "those who will compete" on opening day: They did not include Prince Cupid (Kuhio Kalaniana`ole) who had been an avid competitor earlier, nor any clearly Hawaiian names, even though The Independent had earlier argued that "it is unfair as it is foolish to the Cyclomere Bicycle Track to spread false rumors to the effect that Hawaiians will not be permitted to use it. Common sense should show that for a business speculation such a policy would be ruinous [8/17/1897]."

Prince Cupid and party were listed, however, among the notable attendees among the more than two thousand people who partook of the amusement. Interestingly, the EB reported on 10/25/1897 that the announcer W. Nott "was equipped with a megaphone" but "the performer made blunders in nearly every announcement." He was replaced for the next tourney by a James W. Lloyd who acted as announcer with great satisfaction [EB 10/27/1897]." Incidentally, Prince Cupid entered the one-mile greenhorn race of the second meet, but did not show among the winners [The Indep. 11/2/1897].

On the inaugural day, local riders managed to win a few heats against the foreign "crackerjacks" but one or another of latter took all the finals and "Trilby Fowler delighted the audience with his trick riding [HG 10/26/1897]." After about a month of competing at the Cyclomere, Jones and Whitman decided to stay, the former having found employment with the Press Publishing Co., and the latter being placed "in charge of the bicycle department of Hawaiian Hardware Company's business [HG 11/16/1897]." He then began riding the Tribune bicycle that was being sold by his employer. Newspaper ads reveal that within a year, he first partnered with someone named Eakin to form the Tribune agency and later Whitman & Co. became the sole agent.

Racing events were scheduled on most Saturdays and on some Tuesdays until the end of the season in February 1898. On occasion, foreign riders who coveted cash prizes and side bets came to Honolulu to claim them. Among these were H. F. Terrill from the coast who, as I described three months ago in May 2014, had visited Honolulu for a road race in 1894; and the mercurial Will Martin (a.k.a. Bilmartin) from the Colonies (i.e. Australia) who was dubbed "The Plugger." Accompanying each of the meets were selected musical ensembles that entertained the audience between races. They included the Government (a.k.a. Royal Hawaiian) Band conducted by Heinrich "Henri" Berger, the Hawaiian Quintet (or Quintette), the Kamehameha Glee Club, and Miss Annie Kanoho whom the HG described as "a young Hawaiian girl who has been under the training of Professor Berger [11/17/1897]."

To make a long story short, among the highlights of the season were the following:

Besides Prince Cupid, the first Hawaiian names among the competitors appeared in Dec. 1897. They were amateur A. K. Nawahi and youngster C. Holoua (variably spelled Haloua) who won the boys' (ages 14 to 17) race [HS 12/28/1897]. Both continued to participate and on occasion emerge victorious for several months.

As for Japanese and Chinese racers, a reference to them was announced in the list of upcoming events in Nov. 1897 that included "oriental race, provided not less than six entries are received [HG of 11/9/1897]." An actual run took place at the same meet where Holoua took the boys' trophy. Four Chinese named Ah Tuck, Ah Wai, Y.A. Young and H. Patrick competed among themselves in a half-mile race. In describing it, the HG [1/4/1898] said condescendingly, "four chinese boys started and rode the half [mile] the best they knew how." Ah Tuck was second to Patrick who went on to compete in regular races with the rest of the "legitimate" competitors.

At the same meet, the crowd expected to see "a wellknown Irish character and a Chinese merchant" to be "matched for a mile heat [HS 12/28/1897]," but this turned out to be a comedy routine featuring Jack (or Jock) McGuire and Henry Vierra impersonating an Irish (Dennis O'Rafferty) and a Chinese (Sam Soy) man in "appropriate constume [EB 1/3/1898]." They "kept the crowd laughing for 10 minutes [HG 1/4/1898]," and "both went into the lake a couple of times." At that racially conscious time, Americans held Irish immigrants to the same low esteem as they did blacks and Asians, and all three groups were often the butt of insensitive jokes.

Also on the same program was "Mike Miquel, a young Portuguese lad who is destined to become Honolulu's Trilby Fower," and who gave "a clever exhibition of trick riding."

From a business perspective, "opening of the Cyclomere has had the effect of increasing the value of Kewalo lots [HG 11/5/1897]" but immediately after the end of the regular racing season a newspaper story began with "owner proposes to do away with Cyclomere [HS 3/1/1898]."

SEPTEMBER 2014: CLOSING OF CYCLOMERE

By C. S. Papacostas for the September 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

Last month (August 2014) we saw that the Cyclomere Bicycle Track opened on October 23, 1897 and closed its regular season on February 26, 1898 [Hawaiian Star, HS 2/28/1898]. On March 1, a surprise announcement appeared in the HS under the heading "Track May Go:" Owner C. S. Desky was prepared to fill in the lake and subdivide and sell the reclaimed land if a lessor did not step up soon. He did not say that he lost money, but that he could "not tolerate the bickering" that arose in connection to disputed decisions between competitors and judges. In other words, the enterprise was taking an inordinate amount of his time that he could devote to other business endeavors. The Hawaiian Gazette of March 8 speculated that there was a possibility of constructing a stage on a raft in the lake as part of a potentially lucrative "theater scheme [HG 3/8/1898]."

Instead, a group of five "young men," four of whom were riders, formed a "local hui" to lease and operate the racing track [HG 4/8/1898]. Having lost money after only two meets, "no more racing at Cyclomere so far as the hui of local boys is concerned," said the HG [5/10/1898]. Another potential lessor, Manuel Du Ponte appeared next but Desky decided to close up the park at that time [HS 5/16/1898].

A few days later, however, "W. C. Weedon for Bruce Waring & Co. said that the Cyclomere with lake, grandstand and electric light would be at the disposal of the guests of the Big 100 for any purpose [HG 5/24/1898]." This was in reference to a committee of 100 members organized to welcome and entertain American soldiers ("boys in blue") of the Philippine expeditions during the Spanish American War, coinciding, by the way, with the push to annex the islands. In its "Retrospect for 1898," the Hawaiian Annual explained, "facilities and conveniences of the Hawaiian Islands were tendered by the government to the United States, and Honolulu proved an acceptable way station to her in moving forward the large bodies of troops by all the available steamships that could be secured or pressed into service as transports."

Notably, "additional to several detachments of troops touching here en route to Manila, numbering in all 21,003 men, there arrived for station at this point a corps of Engineers." According to an article titled "Spanish American War Sites in Honolulu" that appeared in the Hawaiian Journal of History (Vol. 39, 2005), "the engineers were sent to build a military post and to survey strategic locations such as Pearl Harbor." They initially shared a temporary camp at the Kapi`olani Park racetrack. The Annual also informed its readers, "the crowded conditions of the troops on the transports resulted in the development of a number of fever cases and other ailments by the time of reaching this port. This led to the organization of a Red Cross Society by some 300 of the ladies of Honolulu, on June 6th, to minister to the sick and distressed; securing and fitting up for hospital purposes the Child-Garden cottage, on Beretania street... till the establishment of the Military Hospital at Independence Park, which opened August 15th." The Philadelphia Medical Journal of August 6. 1896 anticipated this hospital: "It is the intention of the Government authorities to shortly establish a military hospital in Honolulu, upon the grounds known as Independence Park."

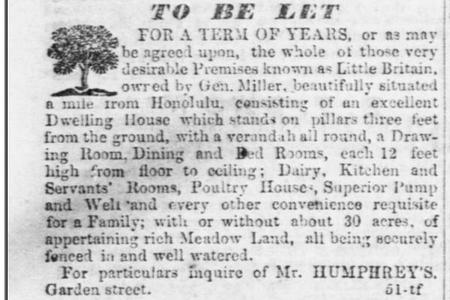

Having an interesting history, "Independence Park" on King Street in Pawa`a (widely reported as being "southeast of the corner of Sheridan and King Streets) was called "Little Britain" until July 4th, 1894 when its then owner, J. N. Wright, renamed it during an American Independence Day celebration; it was previously the site of the residence of Captain George H. Luce, first mate on Bark "Eureka" and for many years tax collector for the District of Honolulu. A portion of this land that stretched from King Street to today's Ala Moana Shopping Center location (known as Malo`okahana), had been purchased by British Consul William Miller, who had his country residence there (see Royal Patent Grant Number 2341, dated March 20, 1857); Miller, who arrived in 1844, followed Richard Charlton, instigator of the infamous Paulet Affair. An 1886 32.96 acre Little Britain plat map by M. D. Monsarrat (Reg. 0976) shows a stone wall on the western boundary where Sheridan Street is today and Ke`eaumoku Street terminating on King Street in the middle of the parcel's King Street frontage.

As an aside, this is how the parcel was described in a newspaper advertisement seeking to rent it: "To be let for a term of years, or as may be agreed upon, the whole of those very desirable Premises known as Little Britain, owned by Gen. Miller, beautifully situated a mile from Honolulu, consisting of an excellent Dwelling House which stands on pillars three feet from the ground, with a verandah all round, a Drawing Room, Dining and Bed Rooms, each 12 feet high from floor to ceiling; Dairy, Kitchen and Servants' Rooms, Poultry Houses, Superior Pump and Well and every other convenience requisite for a Family; with or without about 30 acres of appertaining rich Meadow Land, all being securely fenced in and well watered."

To support the new Red Cross Society, "a blue ribbon bicycle meet will probably be given at Cyclomere park for the benefit of the new Red Cross Society," said the HS [6/7/1898]. To this end, "through the kindness of Bruce Waring & Co. the track and lights are given free of charge [and] the Government Band will probably be in attendance [EB 6/8/1898]." Held on June 25, the event "netted the treasury of the Red Cross Society about $275 [EB 6/28/1898]." By January 1899, the hospital was practically abandoned [HS 1/20/1899].

The Cyclomere park was subsequently leased to Manuel Du Ponte who reopened it on the following July 4th. To boost revenues, the new management began to offer other diversions such as tug-of-war contests, but to no avail for on July 30 the EB headline read "Cyclomere at an End: Track is now being torn up by Gang of Men." On January 9 of 1900 the HS reported that Theodore Hoffman "secured a 100x360 foot location in the site of old Cyclomere Park ("Paka Cyclomere" in Hawaiian language papers) for a new ice plant and cold storage, the Oahu Ice Company. The Independent [1/10/1900] declared "Within three months Honolulu will have another ice plant which will be under the able management of Theo. Hoffman. There is no reason why Honolulu should depend on only one company and submit to the exorbitant prices demanded by the monopoly." Hoffman, by the way, had been manager of the Hawaiian Electric Co. since Sept. 1, 1894 and ice manufacture and cold storage facilities were a major part of the company's operations [Pacific Commercial Advertiser 3/10/1897].

The Park was subdivided into lots for sale by Bruce Waring & Co. Incidentally, to this day, lots in the subdivision are still identified as belonging to the all but forgotten Cyclomere tract!

The Park was subdivided into lots for sale by Bruce Waring & Co. Incidentally, to this day, lots in the subdivision are still identified as belonging to the all but forgotten Cyclomere tract!

In closing the story of Cyclomere and the early days of bicycling in Honolulu, I offer the following tidbits:

- Bicycle racing had resumed at Kapi`olani Park [e.g., HG 1/1/1897].

- Someone composed a "Cyclomere March" that Professor Berger performed [HG 2/15/1898].

- A "police on wheels" was organized consisting of teams "one a haole man and the other a native" to "put a stop to some of the assertions that are made against police officers who go single handed to make an arrest [HG 11/16/1897]."

- Purchasers of 26 lots at Kewalo who had been given deeds warranting the properties as free from encumbrances were "stuck" with an outstanding mortgage that Desky failed to pay [HG 7/12/1904].

- The tax assessor ordered the confiscation of bicycles without a license tag [HS 5/28, 1907].

- It was unlawful for a bicyclist to carry while riding upon any street anything weighing more than five pounds [EB 9/2/1909].

- A proposed traffic ordinance provided that "bicycles and similar vehicles shall not be allowed to approach dangerously near other moving vehicles [Star Bulletin, SB 3/18/1914]."

- Bicycles were included among the vehicles requiring "a gong, bell, horn or any sound signal device to give warning," but "not be used to make any unnecessary noises [SB 6/3/1914].

NOVEMBER 2014: MAUNA KILIKA AND MARKET HOUSE ARMORIES

By C.S. Papacostas for the November 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

In May of last year (2013) I promised to get back to the story behind the Armory of the National Guard of Hawaii that stood where today's State Capitol is located. At its location, on the Waikiki side of Miller Street (makai of Beretania, now gone) that divided the block from Richards to Punchbowl Streets in two halves, was a Drill Shed and Armory that was erected in 1886 [Daily Honolulu Press 4/7/1886]. To make room for the Capitol building which opened on March 16, 1969, the fortress-like `Iolani Barracks (Halekoa) that had been built before the Shed in 1870-71 next door was moved, block by block, to the adjacent Palace grounds.

As a legislator put it in 1890, Hawai`i’s military was composed of companies existing "under a law different from any elsewhere [Hawaiian Gazette, HG, 7/8/1890]." At any given time, there were the regular troops, several uniformed voluntary militia companies, paramilitary but government-supported forces, and armed groups and clubs of varying persuasions and political affiliations. The detailed evolution of these groups would be of interest in many quarters. However, I will be selective in my reporting that follows, keeping in mind that my present objective is to talk about the story behind the Armory and not the military history of Hawai`i.

An armory in the modern sense was clearly part of the Honolulu Fort (1816-1857) that gave Fort Street its name and served many other functions also, including as residence for the Governor of O`ahu and as a prison. It was located below the intersection of Fort and Queen Streets very near the shoreline prior to the reclamation of the adjacent area. Interestingly, a building outside the southeast boundary of the fort, designated as the "Armory" in a well-known 1854 sketch by Paul Emmert of a View of Honolulu from the Harbor (No. 1), was better known as "Mauna Kilika" or "Silk Mountain." This 1840 building served a variety of purposes as well, including as a legislative assembly hall, a hospital for foreign sailors, and the meeting place for political and social organizations.

A notable or, for many, notorious paramilitary force was the Honolulu Rifles. Indications are that it had its genesis in an 1852 foreign sailor disturbance: During a quarrel in the fort between an American and a French sailor who had been incarcerated for being intoxicated, a prison guard, Constable Sherman, clubbed the American, Henry Burns, to death. This incident precipitated a riot involving foreign seamen and resulted in the destruction and burning of a building housing "the Harbor Master, Pilot's office, police station, and water reservoir" and "two small buildings adjoining, used as butcher shops [Polynesian, (Pol.) 11/14/1852]." As the Governor of O`ahu hesitated to deploy regular soldiers and "shed blood," a group of mostly foreign residents sought his permission to form a volunteer company to protect their properties and to quell the disturbance. He agreed and provided arms to two groups named "Hawaiian Guards" and "Hawaiian Cavalry" that were later described as "independent companies of foreigners with a few exceptions in the latter company [Pol. 3/19/1853]." More specifically, the two groups were reported to be made up of "foreign residents, naturalized foreigners, and sons of foreigners [Pol. 4/30/1853]." Following the incident, the King thanked the volunteers by saying "I take this occasion to thank you all, as well as the other foreigners, who on a late occasion, mustered in arms in support of my authority of law and order [Pol. 12/4/1852]."

Renamed the "First" Hawaiian Guard, the new organization held training and drill sessions at its armory, said to be near the New Court House, and participated in ceremonies such as a Fourth of July parade [e.g., Pol. 6/24/1854]. The new Court House, by the way, was completed in 1852 and was located on Queen Street outside the fort on its Waikiki side.

A newspaper announcement introducing the Honolulu Rifles appeared in Feb. of 1857: "A meeting of the 1st Hawaiian Guard will be held at their armory... for the purpose of organizing a Rifle Company. Subscribers of the Honolulu Rifles, and all others interested in the formation of a Military Company, are respectfully invited to be present." Subsequently, the Polynesian of Saturday, Feb. 28, 1857 informed its readers that "at a meeting of the Hawaiian Guard at its Armory on last Thursday evening, it was resolved to organize a new volunteer company" named "Honolulu Rifles." Moreover, "some thirty persons, members of the old 'Guard' and others, subscribed their names on the spot." Interestingly, "Minnie Rifles and uniforms to match [were] expected in the 'Raduya,' 110 days out from Boston." The reference here to the "old" Guard (as opposed to a "new" one) is explained below:

These events took place at a time when, by proclamation, the King re-organized the "Royal Guard and Volunteer Forces" of the Kingdom. Among the changes contained in a related Order No. 1 issued by Secretary of War W. L. Green was the disbandment of the Hawaiian Cavalry and its replacement by a new "Leleiohoku Guard," the renaming of "The Prince of Hawaii's Own" volunteer artillery company to "The Prince's Own," and the formation of a new "Hawaiian Guard" volunteer infantry company to replace the "old" one mentioned in the previous paragraph. The entire proclamation and order, dated February 27, 1857, were published in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser [PCA 2/28/1857]. A sibling of the future King Kalakaua and the future Queen Lili`uokalani, Prince Leleiohoku was the heir apparent to the throne at that time.

Thus, a meeting at the armory of the "new" Hawaiian Guard took place in order to organize the Honolulu Rifles volunteer militia that consisted of members of the "old" Hawaiian Guard and others. Encouraging the public to contribute to the support of the Rifles, the Polynesian [3/21/1857] inferred that "His Majesty [had] in a substantial manner evinced a lively interest in this corps." The PCA [3/4/1858] identified the Rifles' Armory as being on Fort Square, that is, the space opened up by the demolition of the fort. Judging by proximity, it may have been the same building where the old Guard had its Armory, but I have not been able to prove this hypothesis.

Shortly thereafter, on June 21, 1858, the trustees of the Rifles' company submitted a petition to the Legislature "setting forth that the building at present occupied by them as an armory is entirely unsuited for that purpose [PCA 7/1/1858]" and a bill was submitted by Rep. Manini of the Military Committee "authorizing the Minister of the Interior to grant Honolulu Rifles the free use of the upper part of the Market House for an armory." By October of the next year, the PCA [10/27/1859] noticed "that the second floor of the market is being converted into a large room to be occupied as an Armory by the Rifles."

Constructed in 1851 by the Government on the wharf-side of Queen Street between Ka`ahumanu and Nu`uanu Streets, the two-story coral building was featured in the same painting by Emmert that included Mauna Kilika: Both are shown below. At the time, the first story was occupied under a long-term lease by a re-organized C. Brewer & Co. The building was often referred to as the "C. Brewer Building" and the adjacent wharf, Pier 12 since 1914, was at that time known as Brewer's Wharf. It was here, by the way, that troops from the USS Boston landed on January 16, 1893 during the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai`i.

The Honolulu Rifles occupied their Market House armory until 1886 when they moved to new quarters previously used by a skating rink and roller coaster enterprise at Manamanama on the makai side of Beretania beyond its intersection with Punchbowl Street [Daily Press 8/12/1886].

DECEMBER 2014: SKATING RINK ARMORY

By C. S. Papacostas for the December 2014 issue of Wiliki o Hawai`i

This is a continuation of my previous article tracing some major government-supported armories in Honolulu, leading to one that had to be razed to build the current State Capitol which opened in 1969.

Since 1859, the Honolulu Rifles, a volunteer militia company, had been using, free of charge, the second story of a government-owned Market House on the wharf-side of Queen Street between Ka`ahumanu and Nu`uanu Streets. The wharf was called Brewer's Wharf and the building was also known as the C. Brewer Co. building owing to the fact that that company had signed a long-term lease for use of the ground floor.

On Aug. 10, 1886, the Hawaiian Gazette (HG) announced "the Honolulu Rifles have decided to lease the Central Park Skating Rink for an Armory" and on Aug. 19, the Daily Bulletin (DB) said, "the Honolulu Rifles... assembled at the old armory last evening... Having shouldered arms and formed the line of march, Mr. W. King drummed the Rifles to their new armory formerly the Central Park Skating rink, where they were introduced to their new captain, Mr. V. V. Ashford." Located on the makai side of Beretania beyond its intersection with Punchbowl Street, the Central Park Skating Rink and Roller Coaster was dubbed a little more than a year earlier as "the leading pleasure resort of our city [DB 3/30/1885]." It operated in competition with the Yosemite Skating Rink on Queen Street and boasted about offering special skates designed to avoid oil stains on the wearers' clothes [DB 3/31/1885].

Apparently, skating had become a popular sport at the time, despite the fact that The Friend of April 1885 contained the opinion of six medical practitioners from Boston who characterized skating rinks as the source of many physical and social ills. Among them were an atmosphere "poisoned with scores of breaths," irritation of the mucous membrane by fine particles of dust, "spinal affection" along with "protracted invalidism, and some times spinal meningitis," and stiffened and swelled ankles, a condition known as "skating rink ankle." In addition to broken arms and limbs, the article cited the danger of "elopement of young girls, often with married men, who leave wives and children behind..., a natural result of the promiscuous gathering at the rink." Perhaps it was this last reason that motivated the Central Park Rink in Honolulu to declare "the hoodlum element strictly excluded!"

By February 1886 the press averred that "the country [was] without a doubt amply supplied with facilities for indulging in the dubious pleasure of skating. On the completion of Kapahau rink, the Hawaiian Islands can boast of seven such places [DB 2/11/1886]," three of which were on the Big Island. Nevertheless, the Central Park facility ended up succumbing to its competition and closing its doors, despite changes in management and attempts to increase patronage with attractions such as skate and bicycle races. A supposition by the same newspaper that "the Central Park rink will probably be rented by the Government for the Honolulu militia [DB 3/11/1886]" proved to be accurate.

The Kingdom's armed forces, consisting of regular paid troops and several volunteer militia groups went through several reorganizations over the previous decades, the detailed reporting of them being beyond our scope here.

In 1874, the Legislature decided to abolish the Rifles and they were disbanded by order of the Governor of O`ahu [Pacific Conmmercial Advertiser, PCA, 2/21/1874], donating $453.81 that remained in their treasury to the Queen's Hospital [PCA 5/16/1874]. Ten years later, a new volunteer military group petitioned the Government to organize, and the King suggested they adopt the name "Honolulu Rifles [DB 3/6/1884]." Approved by the Cabinet, the new entity began where the old one had left off. In 1887, the Rifles took an active role in the imposition of the "Bayonet Constitution" that eatablished a constitutional monarchy and Thrum's All About Hawaii listed the following

Volunteer Military Companies: Prince's Own, Leleiohoku Guard, Mamalahoa, King's Own, Honolulu Rifles and Queen's Own.

Within the Honolulu Rifles there was in 1887 "a proposition of forming a Portuguese company [and] some dozen or more young men of a superior class put down their names as the nucleus of the new Portuguese militia company [DB 4/4/1887]." Two weeks later, "no less than thirty-two Portuguese mustered for drill at the Honolulu Rifles' armory [DB 4/17/1887]." A year later, the Daily Bulletin [6/22/1888] described the Rifles' Armory as "a hall which, in addition to being a drill shed, fulfills the purpose which no other hall in the town is capable of doing to the same extent." Capable of holding large events such as formal balls and mass meetings, "the Rifles' Armory has come to be regarded as a public hall for public purposes, as much as an armory and drill room for the volunteers."

In April of 1890, company B of the Rifles' Battalion rented a hall in the McInerny building located at the mauka-ewa corner of Fort and Merchant Streets "to be occupied as the company's armory [DB 4/3/1890]," a move that elicited the following editorial comment in the following day's DB: "Why should Company B, Honolulu Rifles be permitted to leave the Battalion Armory and, with consent of the Ministry and the support of some merchants, establish itself a would be Praetorian guard by private means with private headquarters?"

Nevertheless, Company B "had their first drill in their new armory on Fort street [HG 4/29/1890]" and, soon after, "ornamental locks have been put up at one end of the room for the entire company and each person has a key to his respective locker. A piano has been rented, and boxing gloves and other means of exercise are to be introduced for the healthful amusement of the boys [DB 5/7/1890]."

During Legislative debate in June, royalist Rep. R. W. Wilcox said he had been told that "Mr. Bishop paid the expenses of Company B, with the object of dethroning the King and putting a missionary on the throne [DB 7/1/1890]."

The smell of overthrow was in the air!

Following the legislative debate, "the Military Committee of the house are of the opinion that for the peace and safety of the country no such military organization as the Honolulu Rifles should be allowed to exist, and therefore recommended its disbandment [DB 8/22/1890]. By the end of the month, references were maded to "the late Honolulu Rifles [DB 8/30/1890]." The Battalion may have been disbanded but its members remained: According to Rep. Bush of the Provintial Legislature, "although the Rifles had been disbanded, they were keeping up their organization under the guise of athletic clubs [HG 7/29/1890]." By November, the newly formed Honolulu Athletic Association had already "secured a lease on the Rifles' Armory on Beretania street where they have lately made numerous improvements and alterations [DB 11/8/1890], including "the two mauka company rooms have been thrown into one," two bath tubs and showers [were] erected in the makai room, and lockers were put in [HG 11/11/1890]. Two years later, the building housed the Honolulu Cycling Co. that featured skating and a bicycle riding school [DB 9/9/1892].

The Rifles' last armory on Beretania Street became the locus of intense anti-royalist activity during the subsequent events that resulted in the overthrow of Queen Lili`uokalani in January 1893. Its location is shown on the map below, whereas Brewer's Wharf where the Rifles had occupied the second story of the Market House previously is at the lower left of the same map.